On the final day of the Deep Sea Minerals conference in Bergen in April, a panel of experts explored the future of deep-sea mining.

Moderated by Jon Hellevang (R&D Manager at GCE Ocean Technology), the panel consisted of Nathan Eastwood (Partner at Watson, Farley & Williams), Annemiek Vink (Research Associate at BGR), Hans Petter Klohs (Executive Board Director at Adepth Minerals), Graham Talbot (CEO at Wetstone) and Niels Verbaan (Technical Services Director (Hydrometallurgy), Metallurgy and Consulting at SGS Canada).

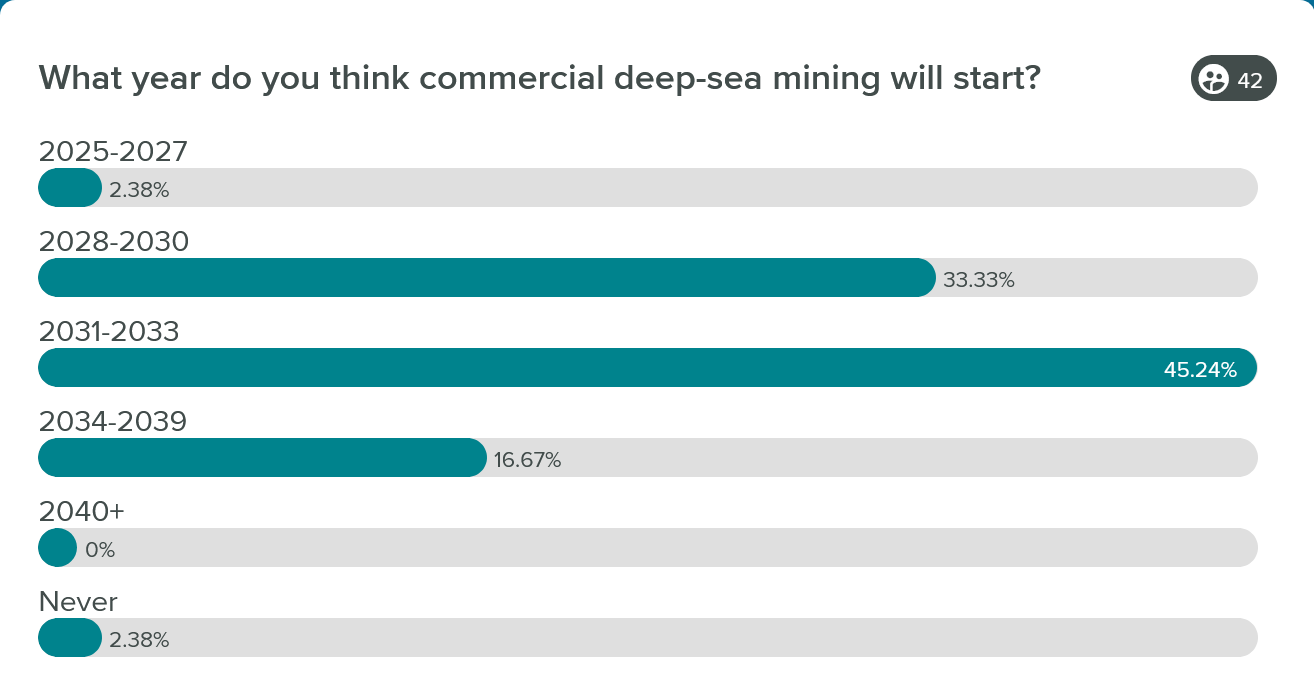

A number of polls were performed during the debate, adding audience interactivity and instant feedback to the on-stage conversation.

Early polls showed most attendees “somewhat positive” about seabed mining, considering legal aspects, environmental challenges, and costs compared to onshore mining as the biggest hurdles for the industry.

Land vs. sea

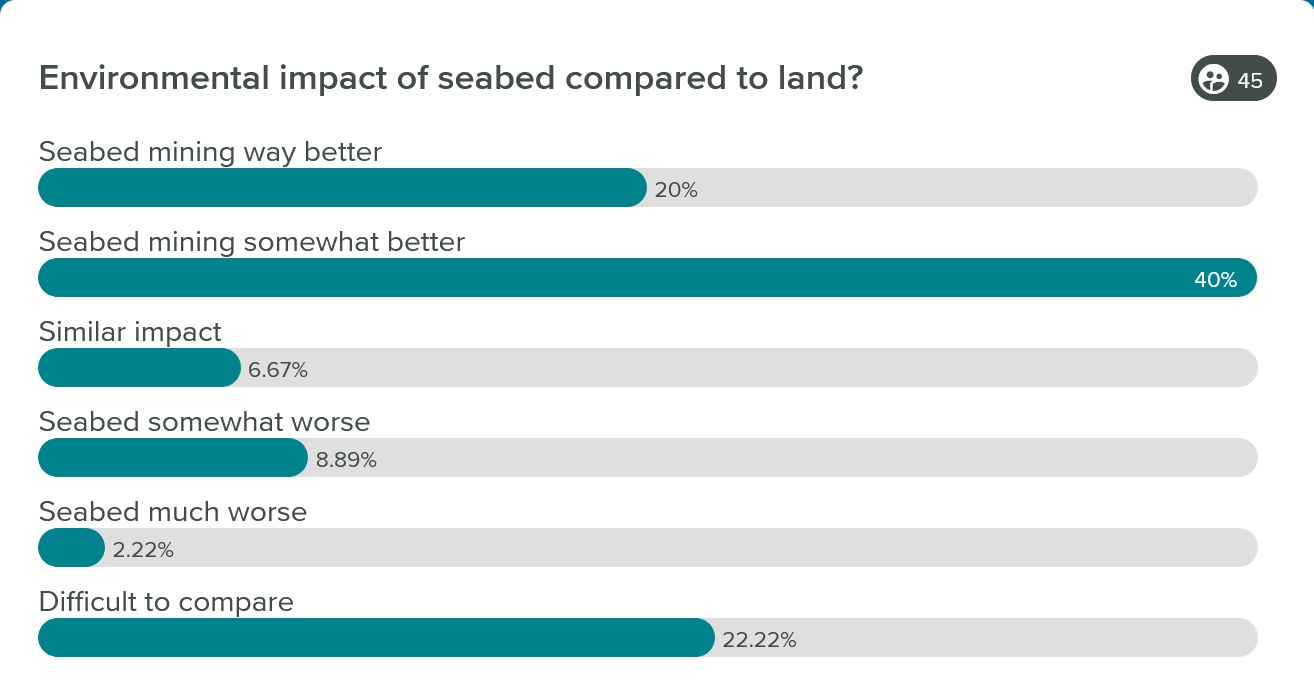

When asked about the environmental impact of seabed mining compared to land, 60 per cent answered that seabed mining is “way better” or “somewhat better”, while 22 per cent called it “difficult to compare”.

Vink, Talbot, and Verbaan agreed that comparing land and sea mining is complex due to differing impacts, but each offered distinct caveats.

– We need good, robust sets of baselines to be able to advance towards mining, we need to know more about diversity, connectivity of species – we need basic information on how the ecosystems functions, Vink commented.

Still, the biologist considered the environmental concerns to be addressable.

– I was a bit surprised to see that more than 40 per cent of the people here think environmental challenges are the main hurdle moving forward. Environmental issues are manageable, but we do need to get a lot more information.

Talbot, backing the majority, stated:

– If I didn’t believe that seabed mining was a far better solution, I probably wouldn’t be sitting here today.

He argued for a future-focused view – seabed mining should be compared with future mines on land. As land ore grades decline, onshore mines will require larger areas and more ore to maintain, let alone increase, output.

– Mining will encroach on more sensitive areas, and those are the ones we need to compare to deep-sea mining. I believe seabed mining can be a better alternative, but we have a lot of work to do.

Although some companies have performed tests on marine ores in processing facilities, Verbaan added, we still have limited knowledge regarding the amount of tailings that will be produced, energy and reagent consumption, etc.

He agreed with Talbot that land mining can have a devastating environmental footprint, and with Vink that the social aspect also needs to be considered, such as child labour at cobalt mines in Congo.

Klohs praised Adepth and the EMINENT project’s approach:

– Based on the indications from our research and tests so far, I believe we can perform better than many mines on land in terms of costs, processing, and environmental impact.

Concluding on the environmental aspects of the discussion, Vink pointed out that each seabed mineral resource (nodules, sulfides, and crusts) each poses unique challenges, varying by region and project.

Legal limbo

The International Seabed Authority’s (ISA) long-awaited mining code – a framework for deep-sea mining in international waters – has been much discussed recently. The ISA governs international waters (the Area) under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

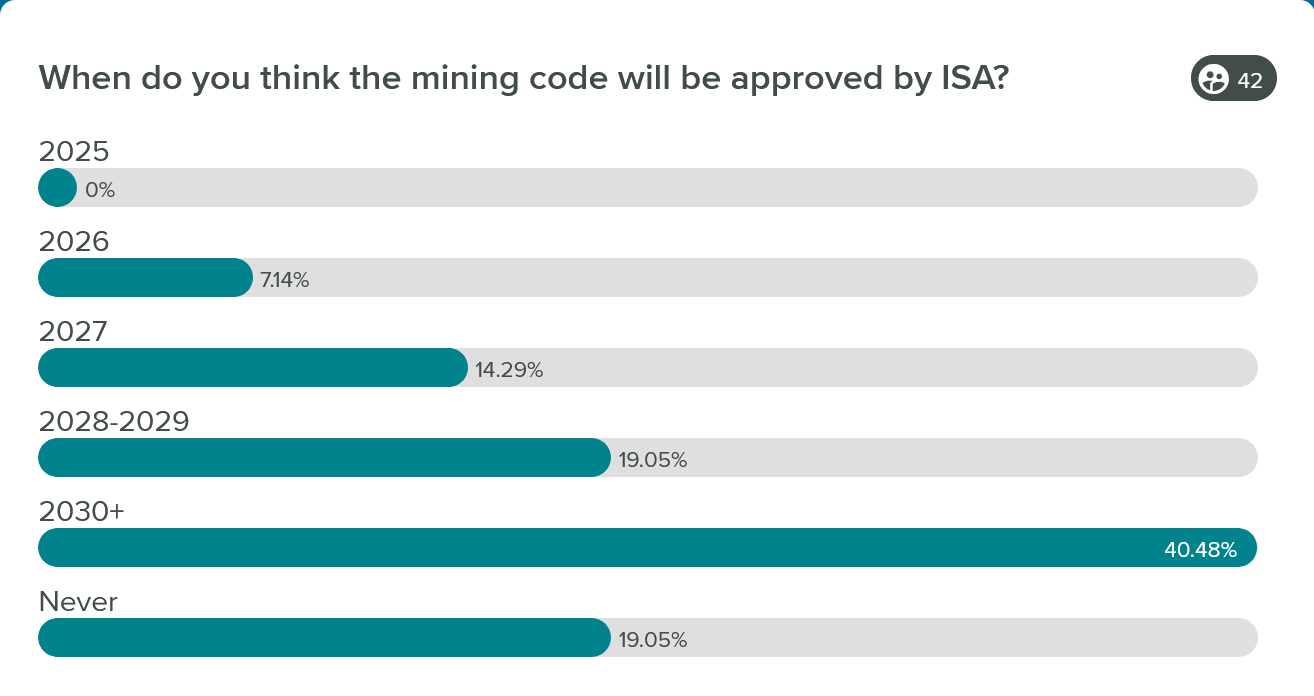

The mining code also sparked discussion during the panel debate. When asked when it might be approved, most attendees picked 2030+. Close to 20 per cent said “never”.

Eastwood, representing legal expertise, rejected scepticism:

– It’s a clear obligation under the convention that they do have to adopt the regulations. It’s not optional. I would probably fall within around 2028-2030, Eastwood guided, pinpointing the delays to “diplomats” going through and negotiating the code line by line.

The ISA had previously targeted 2025 for completing the mining code, however, the newly elected Secretary General Leticia Carvalho, pointed out already last year that the work may still require some years.

Frustrated by the delays, The Metals Company (TMC), has submitted an application for commercial extraction under the U.S. Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA) of 1980, bypassing the ISA, potentially weakening its authority.

– It’s a viable path (DSHMRA) and I think under international law it’s a path that is open to those who want to pursue it, Eastwood affirmed.

Vink stressed the ISA code’s necessity, saying:

– It’s of vital importance for any state or company wanting to work in international waters, especially for those member states that have signed the convention. I think it is the only option to move forward, given the convention’s focus on equity, including common heritage of humankind and level playing fields for contractors.

Talbot, whose firm is only looking to invest in projects in national waters (exclusive economic zones, EEZs) and not international waters, believed that the uncertainty and delays impact the overall risk assessment in terms of financing. Investors don’t like risk, and companies that are pursuing projects in the Area would have more difficulty obtaining financing.

That could actually be good news for companies operating in national jurisdictions.

– We may see more collaboration within the EEZs while we wait for the ISA, he suggested.

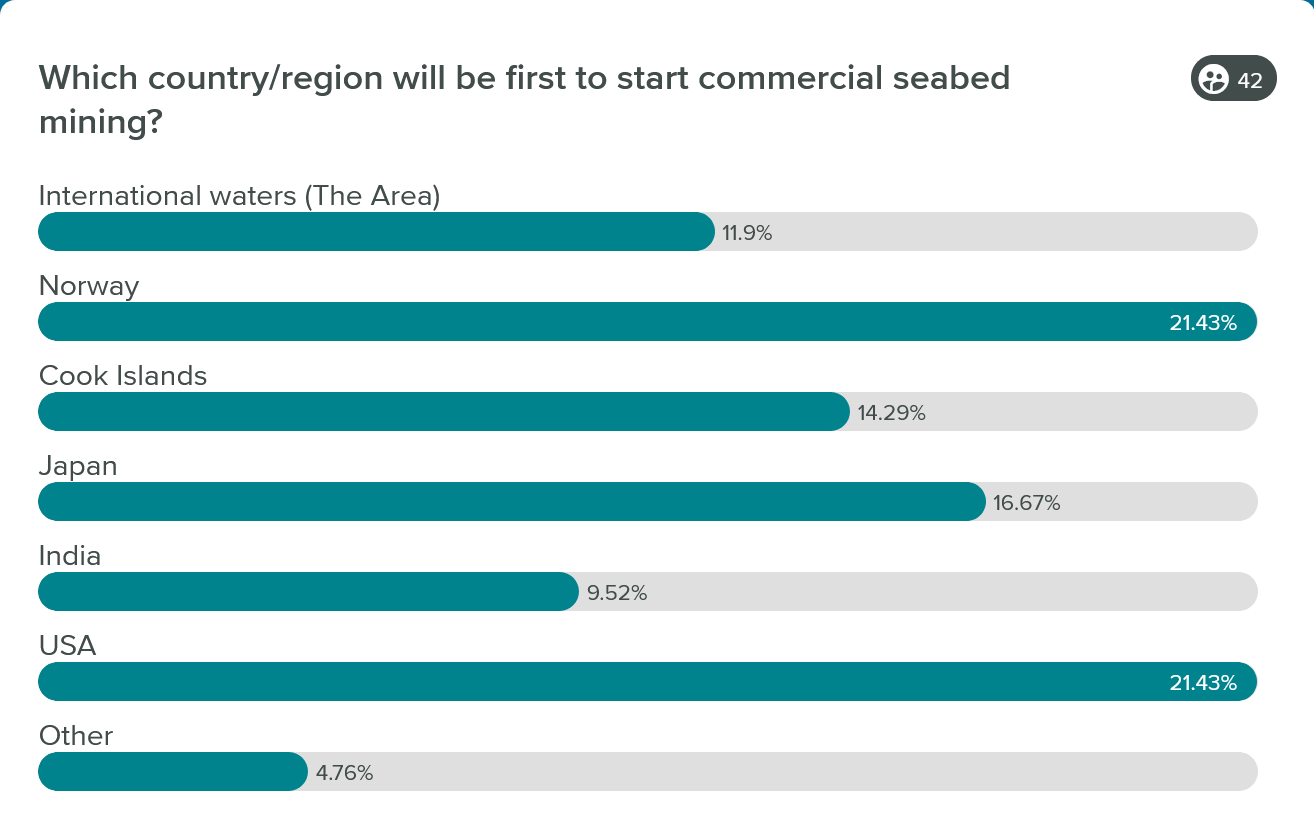

EEZs with known marine mineral resources include Norway, the US, Japan, India, and the Cook Islands.

When asked about which country/region will be the first to start commercial seabed mining, Norway and the US got most votes (21 per cent each). 12 per cent of the respondents chose international waters.

– Norway can take the lead, stated Klohs, arguing that the country has extensive experience and an impeccable track record in regulating its offshore oil and gas industry.

He indicated that we might see mining projects in Norway coming to fruition around 2030, given that exploration activities will get green lit soon. In December last year, the Norwegian government postponed the first licensing round as part of a budget agreement.

Talbot speculated on the US or India as the first mover.

Pragmatic optimism

Wrapping up the panel debate, some panellists pegged the ISA as a persistent challenge.

– My concern is that if mining permits are given to companies through the US route, it could lead to the death of the ISA, undermining decades of work on environmental and social regulations. It is a worrying development, Vink said.

Eastwood spotlighted potential inequity in the upcoming ISA mining code. Warning that test and pilot mining could cost hundreds of millions of dollars prior to commercial operations, he argued this financial barrier would violate UNCLOS promises of making the Area available equitably for developing nations.

Talbot mixed optimism with pragmatism:

– I’m super excited about the industry and where it’s going, but it’s not without its challenges and a huge amount of hard work is still needed. What we can achieve for the world if we are successful is phenomenal.

He urged focus, stating that “we understand enough about what we don’t understand, so we can now focus on de-risking to completion at one place at a time”.

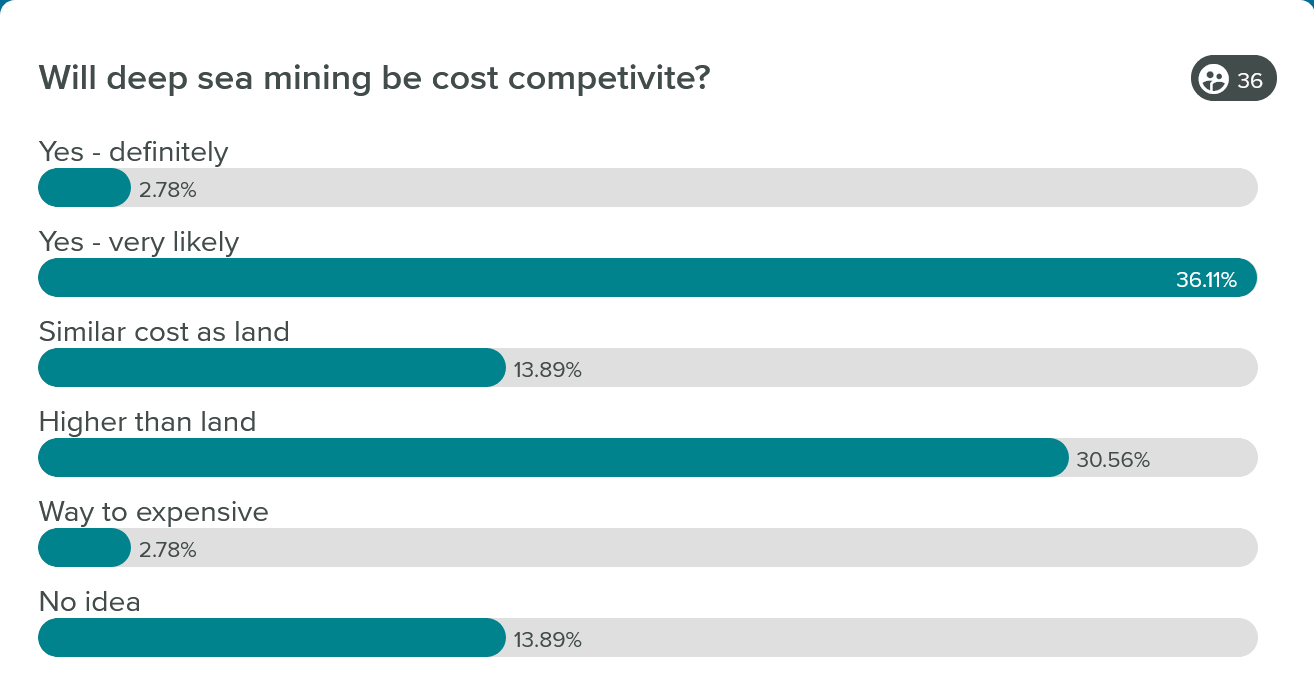

In terms of cost competitiveness, Talbot believed that seabed mining projects would be economically marginal at first but gradually move down the cost curve. Some of the panellists credited the expected cost competitiveness to the elevated metal grades observed in marine ores.

Offering the Norwegian perspective, Klohs held firm:

– Our data on resources, technology and environmental baseline from the Mohn’s Ridge is so far positive, leading us to believe that we can realize high commerciality with low impact.

The industry recognises the challenges and hard work ahead but envisions a clear path towards realizing deep-sea mining.

When might we see the first commercial seabed mining project? Polls pegged this to 2028 – 2030 (33 per cent) or 2031 – 2033 (45 per cent), with 2 per cent saying never.

Note: The poll results were based on 30 – 50 respondents that may be representative for the deep-sea minerals industry and surrounding ecosystem, but certainly not for the broader society.